Build Log

We are currently building the Architect Layer of Entropy. This is the engine responsible for the genesis of our simulation agents. It is not enough to simply spawn “1,000 agents”; the simulation is only as valuable as the fidelity of the population inside it. If the agents are caricatures, the data is noise.

Our goal is epistemic honesty. This doesn’t mean every population has perfect data: some groups, like German Surgeons, have rich statistical registries, while others, like specific sub-rural communities, may not. Epistemic honesty means generating agents based on the best available evidence and being transparent about the rest. When data exists, we ground the agents in it. When it doesn’t, we interpolate from adjacent populations rather than hallucinating from a generic template.

Getting there required us to dismantle our original architecture and rebuild it from first principles.

To illustrate this evolution, we will track a single, complex example throughout this post: Simulating German Surgeons adopting a new AI diagnostic tool.

The Fixed-Core Fallacy

In the first iteration of Entropy Architect, we operated on a hidden assumption about what constitutes a “human agent.” We built a system where the core identity was fixed, and only the situation was dynamic.

We defined a rigid schema based on standard social science models. Every agent, regardless of their population, had to possess specific Demographics, Big Five Psychographics, and a set of Cognitive biases.

This approach wasn’t wrong, the schema was academically sound, but it forced irrelevant precision. When simulating a specialized population like German Surgeons, the system was compelled to generate scores for traits like “openness to experience” or “media hours daily,” even if those traits had little bearing on the simulation’s goal (e.g., adopting a new medical tool).

Worse, by locking the core identity into fixed buckets, we often missed key drivers specific to the population. For a surgeon, traits like clinical tenure, institutional rank, or peer influence network are far more predictive than generic personality scores. Yet, in v1, these critical professional traits were relegated to a generic situation side-bucket, treated as secondary data rather than core identity.

The v1 Surgeon

The Architect is forced to generate a generic psychological profile while the true drivers of surgical behavior are pushed into an un-structured sidecar.

{

"agent_id": "surgeon_492",

# Fixed buckets forced on every agent

"demographics": {

"age": 45,

"education": "doctorate" # Generic bucket

},

# Irrelevant precision for this use case

"psychographics": {

"openness": 0.65,

"conscientiousness": 0.88,

"neuroticism": 0.32

},

# The core professional traits are second-class citizens

"situation": {

"profession": "Neurosurgeon",

"years_experience": 15,

"institutional_rank": "Senior Physician"

}

}

Assessment: The agent has a high-fidelity generic personality but a low-fidelity professional identity. The architecture prioritizes the wrong attributes.

Shift to Dynamic Discovery

We realized we needed to make the entire definition of the human being variable, not just their situation. We scrapped the fixed core. In v2, we moved to an architecture of Dynamic Discovery. When a user requests a population, the Architect Layer reasons from first principles: “What defines this specific population?”

For German Surgeons, the system discovers that Bundesland (State), Facharzt (Specialty), and Years of Practice are the governing variables. It launches agentic research tasks to find real-world distributions for those specific attributes. The schema is no longer a pre-defined template; it emerges from the research.

The v2 Base Identity

The irrelevant generic data is gone. The agent’s schema is now completely grounded in its professional reality.

{

"agent_id": "surgeon_492_v2",

# Discovered attributes specific to this population

"bundesland": "Bavaria",

"facharzt_specialty": "Cardiothoracic",

"institutional_rank": "Oberarzt (Senior Physician)",

"years_of_practice": 18,

# Research-grounded salary band for this specific rank/specialty

"annual_gross_salary_eur": 145000

}

Assessment: High fidelity, but static. We have a perfect picture of who the surgeon is, but we lack the behavioral attributes to simulate what they will do in a specific scenario.

The Efficiency Paradox: Identity vs. Context

While v2 solved the grounding problem, it introduced a new challenge.

A human being is not a monolith. We have an Identity (durable traits like age, training, and history) and we have a Context (transient traits like stress levels, adoption propensity, or price sensitivity regarding a specific event). To simulate reactions to a new AI tool, we shouldn’t have to re-research the demographics of the German medical system every time. That data is durable and expensive to acquire. We only need to understand their specific “AI Adoption” traits.

If we merge the layers into one giant research task, we waste compute re-discovering the basics for every simulation run. If we keep them fully separate, we lose causality—we run the risk of generating a senior, traditionalist surgeon who is inexplicably a high-risk tech adopter because the two research phases didn’t talk to each other.

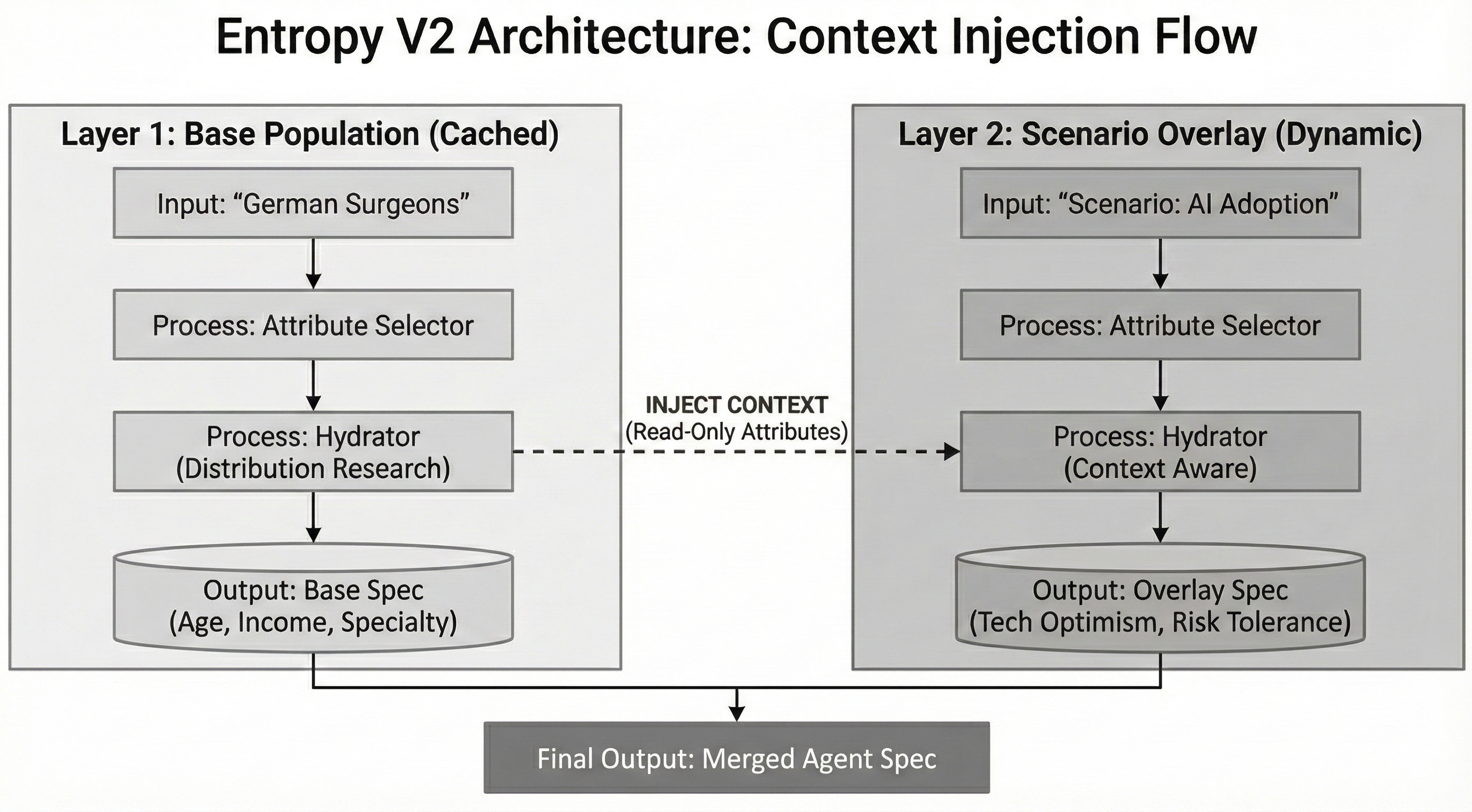

We solved this by splitting the agent specification into two distinct, interlocking layers: Base Identity and Scenario Overlay. The architecture now utilizes a “Context Injection” pattern to maintain causality without sacrificing efficiency.

- The Base Layer (Cached): We research the durable population identity once (the v2 example above). This is stored and reusable.

- The Overlay Layer (Dynamic): When the “AI Adoption” scenario is run, we spin up a new research pass only for behavioral attributes related to that scenario.

The uniqueness is in the injection. When the Architect researches the Overlay, we feed it the schema of the Base Layer as read-only context. The LLM “sees” that the population has attributes like years_of_practice and institutional_rank. It doesn’t change them, but it builds its behavioral dependencies against them.

Solving the Variance Problem

This brought us to the final mathematical hurdle in generating the final agent: The Clone vs. Chaos problem.

When linking the layers (e.g., linking Base years_of_practice to Overlay adoption_likelihood), we must be careful how we define the relationship to maintain realism.

- The Clone Problem: If we use a pure mathematical formula (e.g.,

Adoption = 1.0 / years_of_practice), every surgeon with exactly 18 years of experience behaves exactly the same. We lose human agency and create clones. - The Chaos Problem: If we use pure random sampling for adoption, ignoring the base layer, we break reality. We generate senior experts with the risk appetite of interns.

We solved this by implementing Conditional Distributions. We don’t simply derive behavior from demographics. Instead, we sample a baseline behavior from a distribution to establish individuality, and then let demographics nudge it to establish causality.

The Final v2 Agent

Here is the final instantiated agent, combining the cached Base Identity with the dynamic Scenario Overlay using conditional distributions.

{

"agent_id": "surgeon_492_final",

# --- Layer 1: Base Identity (Cached) ---

"bundesland": "Bavaria",

"facharzt_specialty": "Cardiothoracic",

"years_of_practice": 18,

# --- Layer 2: Scenario Overlay (Dynamic) ---

# 1. Base Risk Tolerance is sampled stochastically (The "Chaos" element)

# This ensures individual variance: some people are just naturally riskier.

# Sampled from Normal Distribution(mean=0.5, std=0.2) -> Result: 0.62 (Slightly risk-seeking)

"base_risk_tolerance": 0.62,

# 2. The modifier is applied deterministically (The "Clone" element)

# This ensures causality: experience generally breeds caution.

# Rule: If years_of_practice > 15, multiply risk by 0.8 (Senior conservatism nudge)

"experience_modifier": 0.8,

# 3. Final behavioral score used in simulation

"final_ai_adoption_likelihood": 0.496 // (0.62 * 0.8)

}

Assessment: This approach preserves the “Cool Grandpa” effect. The population trends toward realism (older surgeons are generally more conservative due to the modifier), but individual variance remains alive because the base score was sampled stochastically. We aren’t simulating math equations; we are simulating people.

In a follow up post, I’ll explore why this architecture generalizes, and why agent generation is fundamentally a code generation problem.